A federal judge in California is set to rule this fall on whether the foundational Fish Market riddim, better known as Dem Bow, is copyrightable, a decision with multi-million-dollar implications for how the Reggaeton industry credits its Jamaican roots.

Unlike most music copyright disputes, which typically deal with similarities in melody or lyrics, this case focuses on an instrumental. Can a riddim be protected under U.S. copyright law? That’s one of the questions U.S. District Judge André Birotte Jr. will begin weighing on September 26, when he hears arguments on dueling motions for summary judgment in the landmark case.

The lawsuit pits the creators of the 1989 riddim — the late Wycliffe “Steely” Johnson and his partner Cleveland “Clevie” Browne — against a coalition of over 160 Reggaeton artists, producers, and arms of the world’s three largest record labels, UMG, Sony Music, and Warner. Over 1,800 songs allegedly infringed on Fish Market, according to the suit, including mega-hits like Daddy Yankee’s Gasolina, Luis Fonsi and Justin Bieber’s Despacito, Bad Bunny and Drake’s Mía , Pitbull’s We Are One (Ole Ola) , and DJ Snake’s Taki Taki .

A key group of 107 defendants, represented by the firm Pyor Cashman LLP, argues that Fish Market is not original enough to warrant copyright protection. In court filings obtained by DancehallMag, they claim that it is built from common, pre-existing elements or “prior art,” including, among other things, a centuries-old ‘habanera’ rhythm that became a staple in Jamaican church music during the 20th century.

They point to a 2005 interview where both Steely and Clevie admitted drawing inspiration from the “Poco beat” of Pentecostal services. “That Fish Market employed a ‘Poco beat,’” the defendants argue in the filing, “is further confirmed by the fact that the vocal version of the track [the first song to use the riddim] is titled Poco Man Jam .”

But Doniger/Burroughs, the lawyers for Steely & Clevie, argue that the riddim’s originality lies not in the individual drum sounds (its kick, snare, hi-hat, etc) but in their unique “selection and arrangement.” They countered that the defendants have sidestepped this central argument by focusing on isolated elements rather than assessing the originality of the Fish Market instrumental as a whole.

With the case hinging on technical analysis — whether Fish Market is original, whether it’s protectable, and whether it was copied or sampled in each of the 1,800 tracks — both sides have enlisted a roster of musicologists and industry experts.

The experts supporting the defendants include Dr. Wayne Marshall (a US ethnomusicologist and professor), Dr. Joe Bennett (a US forensic musicologist), Dr. Peter Manuel (a US ethnomusicologist and professor), and Paul Geluso (a US music engineer and professor).

For Steely & Clevie, the experts include Hopeton “Scientist” Brown (a Jamaican engineer and producer), Lynford “Fatta” Marshall (a Jamaican engineer and producer), Shaun “Sting Int’l” Pizzonia (a US engineer and producer), Judith Finell (a US forensic musicologist), Dr. Kenneth Bilby (a US ethnomusicologist), Peter Ashbourne-Firman (a Jamaican composer and songwriter), and Clevie, himself, who offered a firsthand account of the creation and originality of the Fish Market riddim.

Interestingly, Clevie, now 65, challenged some defense claims of prior art by rejecting comparisons to earlier tracks such as Lloyd Lovindeer’s Babylon Boops, Chaka Demus’ Bad Bad Chaka, Admiral Bailey’s Come Pon Top and Big Belly Man, and Red Dragon’s Agony. In each instance, the producer highlighted technical differences in rhythmic patterns, instrumentation, and arrangement, arguing that Fish Market featured a distinctive configuration not present in those songs.

He also pointed out that many of those tracks cited by the defense were built on riddims that he and Steely had engineered for other producers like Winston Riley.

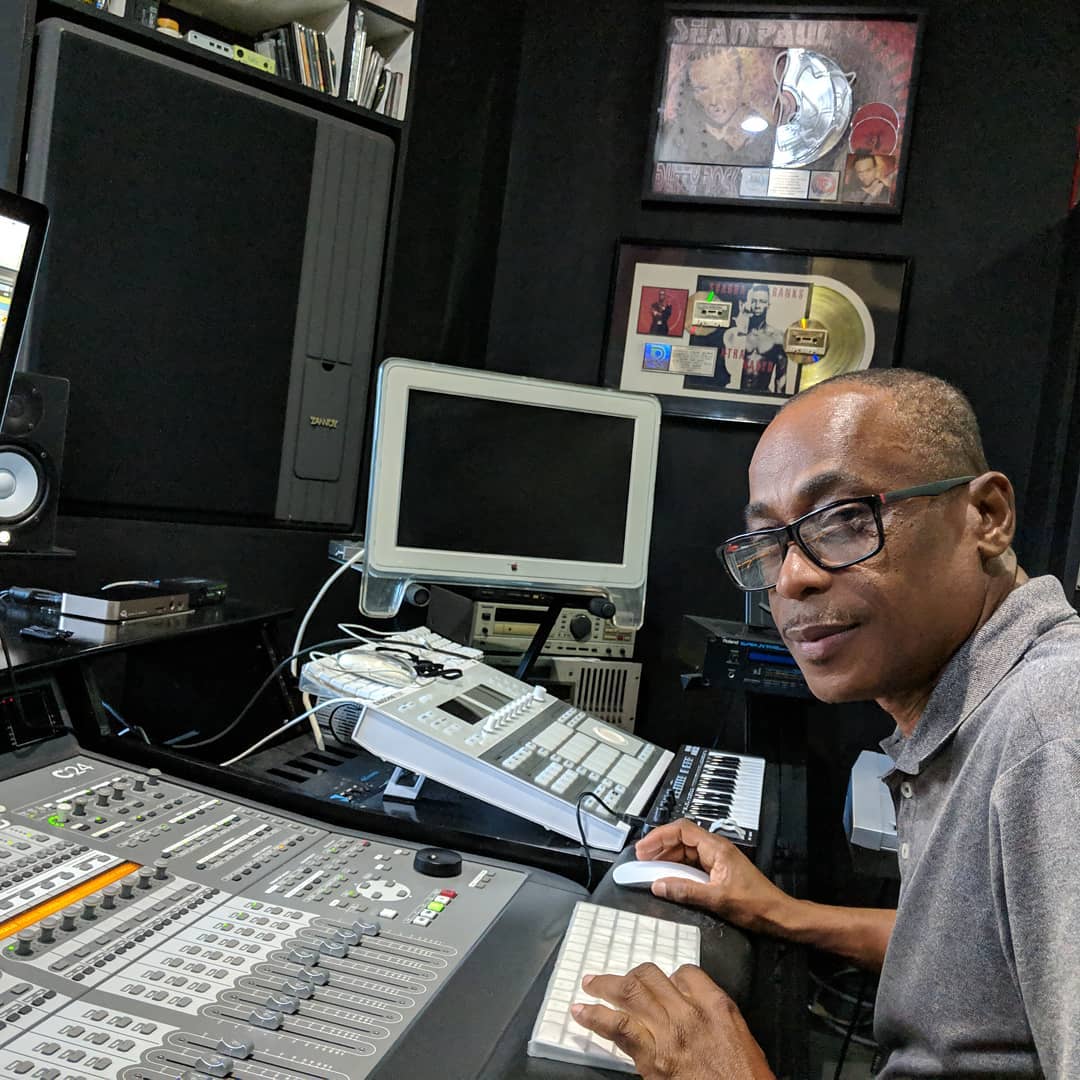

Cleveland ‘Clevie’ Browne

Cleveland ‘Clevie’ Browne

In their motion, filed earlier this month, Steely & Clevie’s attorneys also highlighted what they describe as two contradictions from one of the defense’s own experts, the ethnomusicologist Dr. Wayne Marshall.

They cited a private message from Dr. Marshall, sent to Clevie’s manager Danny Bouten, during an early stage of the case, in which he appeared to validate their claims of originality. “I could never take the other side against Clevie in this case,” Dr. Marshall wrote, according to the filing. “My respect and admiration for him and his work with Steely is too great. I do think there’s merit in his claim of ownership over what has come to be known as the dembow – not to mention various other derivative works based on Fish Market’s various elements . . . I hope, ultimately, that Clevie receives just compensation for the remarkably resonant musical materials he produced.”

According to Steely & Clevie’s filing, Dr. Marshall also previously acknowledged the originality of the popular Diwali riddim based on similar combinations of non-original parts (its tambourine, clapping, and bass drum). They suggested that the same standard should apply to Fish Market.

Steely & Clevie also leveraged the words of Reggaeton’s pioneers against the defendants. The filing shows them quoting Daddy Yankee, who called the beat “creative and inspiring,” while adding, “This drums’ rhythm is what inspired us.” Wisin & Yandel reportedly called the Dem Bow riddim “totally original” and DJ Nelson reportedly stated, “The origins of the dembow rhythm . . . are Jamaican, and the one who made it famous was Shabba Ranks with his song ‘Dem Bow.’”

Roderick Gordon, an intellectual property lawyer who is not involved in the case but has been following it, told DancehallMag on Tuesday that the immediate decision before Judge Birotte is not to determine a final verdict, but to rule on whether the case proceeds to trial or is dismissed, in whole or in part.

“It will be fascinating to see how the Judge handles this application for summary judgment. This type of application is a technical one, essentially seeking to strike out the claim on the basis that there is no legal merit to its foundation,” Gordon said.

The outcome, he added, “will have a landmark effect on the current application of copyright law to many similar claims of originality. Too close to call!”

6 months ago

41

6 months ago

41

English (US) ·

English (US) ·