“Well, it’s politics time again. Are you gonna vote?” Buju Banton chants in his 1997 single Politics Time. In the 1970s and 1980s, streets in sections of downtown Kingston, Jamaica, were battlefields. Garrison constituencies in Trench Town, Tivoli, Rema, Jungle, and Waterhouse were fiercely loyal to either the People’s National Party (PNP) or the Jamaica Labour Party (JLP). Political campaigning often brought bloodshed. Out of this turmoil, reggae — and later dancehall — music thrived not just for entertainment, but as a voice for unity and survival.

I was a youngster living on Sunflower Way in Mona Heights, Kingston, on December 3, 1976, when reggae legend Bob Marley was shot at 56 Hope Road (now the site of the Bob Marley Museum) by unknown assailants. As news broke of the assassination attempt, a collective “Mi cyaan believe it!” reverberated across Jamaica. To put it mildly, we were all in shock. Marley’s wife Rita and manager Don Taylor were seriously injured, while a bullet grazed Marley’s chest and another lodged in his arm.

Marley was scheduled to perform at the free Smile Jamaica concert at National Heroes Park in Kingston just two days later. A flier for the event read: “Bob Marley, in association with the Cultural Section, Prime Minister’s (Michael Manley) office, presents Smile Jamaica — a public concert featuring Bob Marley and the Wailers and the I Threes.” The concert had been arranged to ease political tensions and gang warfare that had engulfed the country in the months leading up to the December 15, 1976, general election.

By 1976, Marley’s popularity was surging across Europe and parts of the USA. He was revered by many and seen as a symbol of freedom. Some speculated that the attack was meant to send a warning that he should not meddle in Jamaican politics. “I do not defend Marxism nor Capitalism. We are strictly Rasta,” Marley once proclaimed in a TV interview.

I found a possible answer to the “Who shot Marley?” question in a Netflix documentary titled Who Shot the Sheriff? When asked by TV host Gil Noble if he knew his attacker(s), Marley replied, “At that time, no.” He later admitted he knew who was responsible, but no one was ever charged. The lingering question remains — was Marley attacked by assailants aligned with one of Jamaica’s political parties, or was it the work of the CIA? The documentary, directed by Kief Davidson (writers Jeff Zimbalist & Michael Zimbalist), intriguingly places infamous Jamaican drug lord Jim Brown, father of Christopher “Dudus” Coke, at the scene of the crime.

Reggae historian and musicologist Copeland Forbes, who recently released his autobiography titled Reggae My Life, narrowly missed being at Marley’s house that night.

“That particular night I was down by the Sheraton Hotel with Don Taylor (Marley’s manager),” he recalled. The two were discussing a January 1977 concert at Madison Square Garden in New York with Burning Spear, Mighty Diamonds, and special guest Black Eagle featuring Denroy Morgan (patriarch of reggae group Morgan Heritage).

After the meeting, Taylor asked Forbes to accompany him to 56 Hope Road, where Marley and the Wailers were rehearsing. He declined, opting instead to visit his mother, whom he had not seen since returning from abroad.

“When I was there (at my mother’s), I heard it on the news… I jumped into a taxi and went up there (56 Hope Rd). The place was cordoned off. Police were there. Bob had already gone to the hospital,” he said.

The 45-minute documentary offered a gripping view of the social unrest that plagued Jamaica in the 1970s. Reports suggest the U.S. government was tracking many pop musicians at the time, including Marley. The CIA was particularly concerned about Prime Minister Michael Manley’s socialist leanings and his relationship with Cuban leader Fidel Castro. Some feared Jamaica could follow Cuba into communism.

The film features never-before-seen archival news footage and interviews with notable figures, including former Prime Minister Edward Seaga, former Information and Youth & Community Development Minister Arnold Bertram, Miss World 1976 Cindy Breakspeare, reggae artist Jimmy Cliff, Nancy Burke, Carl Colby, Tommy Cowan, Vivien Goldman, Diane Jobson, Wayne Jobson, Marley historian Roger Steffens, Allan Cole, and Alvin “Seeco” Patterson, among others.

After the assassination attempt, Marley fled to Nassau, Bahamas, then to England, where he recorded the albums Exodus (1977) and Kaya (1978). Two years later, he returned to Jamaica for the famous One Love Peace Concert, where Marley, Peter Tosh, Dennis Brown, Althea & Donna, Beres Hammond, U Roy, and Jacob “Killer” Miller performed. Following the attack, Marley’s popularity surged. He became reggae’s most powerful messenger. His songs preached love and justice, but in 1978, he turned words into an unforgettable act.

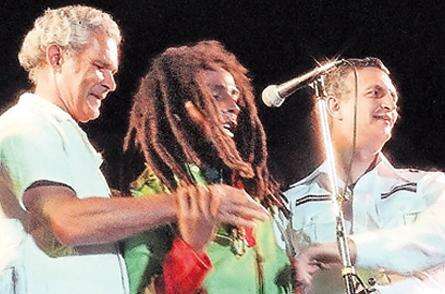

I was among the thousands of youths and reggae heads attending the One Love Peace Concert at the National Stadium in Kingston in 1978. It was my first and only time seeing Bob Marley perform. Organized to cool political tensions, Marley halted his performance, called Prime Minister Michael Manley and opposition leader Edward Seaga to the stage, and raised their hands together above the crowd. It was a bold, symbolic appeal for peace in a nation plagued by political violence. While the violence did not end after the concert, the image of Marley uniting the country’s bitterest rivals remains one of the most enduring symbols of Jamaican resilience.

Peter Tosh, who performed at the concert, took a different approach. His songs like Equal Rights and Downpressor Man directly targeted corrupt leaders and systemic injustice. At the same Peace Concert, Tosh lectured politicians for nearly an hour, refusing to let his potent message be diluted.

By the late 1980s, with political violence now intertwined with drug wars, dancehall took the spotlight. Among its stars was Ninjaman, known for raw, streetwise lyrics. In an unexpected turn, he recorded Nah Go Love It, urging supporters of both the PNP and JLP to lay down arms and stop killing each other. The song resonated with youths in Kingston’s toughest neighborhoods, where the violence was most entrenched.

From Marley’s attempt to unite Michael Manley and Edward Seaga, to Tosh’s fearless chants, to Ninjaman’s street-level calls for calm, these artists proved that reggae and dancehall were more than rhythm and rhyme — they could be a bridge over Jamaica’s deepest divides.

6 months ago

19

6 months ago

19

English (US) ·

English (US) ·